Lately I’ve felt like I’m living in parallel universes. On one hand, I am trying to get the word out of the bias in GenAI, the problems that can cause, and the caution we should be using when these technologies are applied in educational contexts. For example, ChatGPT 3.5 provides lower average writing scores when a student is described as preferring rap music over classical music, and potentially even more so when the music preference is hidden within the writing itself.

On the other hand, I am having a great time playing with GenAI, exploring possible uses for new types of learning, and encouraging others to join me.

As I’ve attempted to reconcile these perspectives, I’ve come to the realization that what may be the most important concept of GenAI in education is Critical AI literacy. Several definitions of AI literacy have been coming out. My favorite is the recent definition offered by Digital Promise:

AI literacy includes the knowledge and skills that enable humans to critically understand, use, and evaluate AI systems and tools to safely and ethically participate in an increasingly digital world.

Revealing an AI Literacy Framework for Learners and Educators, Digital Promise

I like to add “critical” to AI Literacy because it emphasizes analysis and investigation of how it reflects and impacts society. A fantastic related resource is the technoskeptic view presented by Civics of Technology. (Here’s a great overview of this type of thinking).

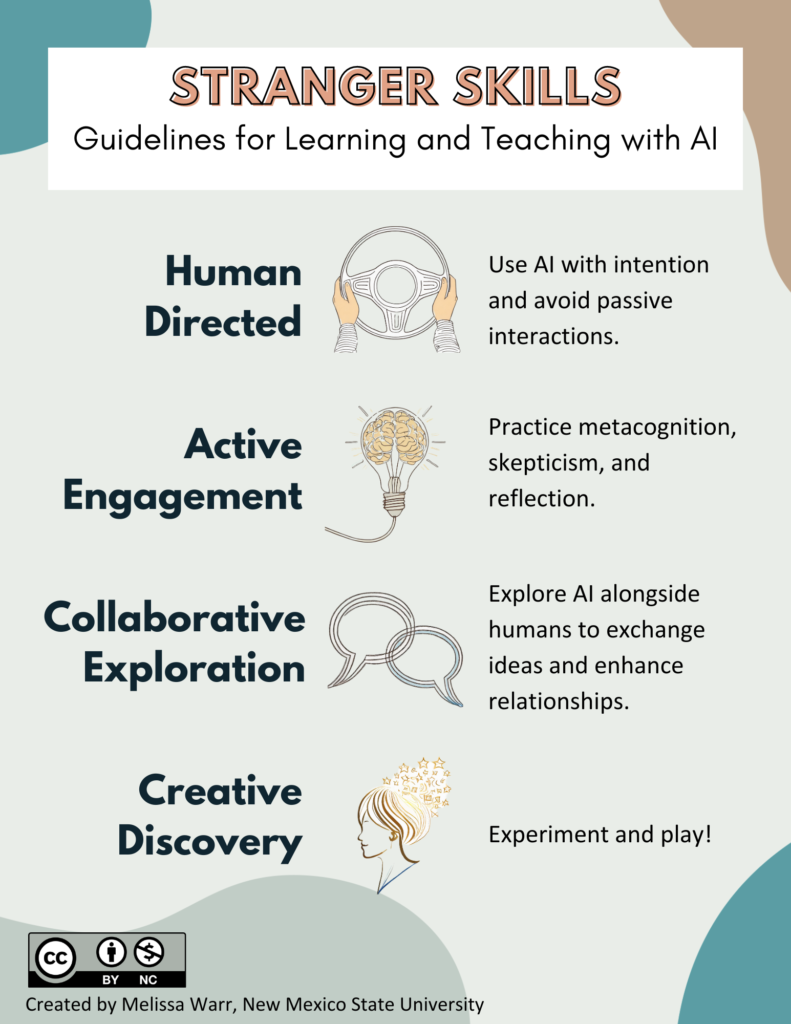

As I’ve thought about what this means for the role of GenAI in teaching and learning, I’ve begun to develop some ideas about what appropriate and effective use might look like.

These guidelines start with recognizing the nature of GenAI--it is, as Punya Mishra explains, a smart drunk intern, a BS artist, and WEIRD (white, educated, industrialized, rich, and democratic). It is an alien intelligence, and one that requires a certain type of thinking and interaction that we are all trying to learn, even as it constantly changes.

Once we recognize that we are dealing with a different kind of tool, a morphing alien intelligence, we realize that partnering with this tool requires new ways of thinking. When used to support learning, following these guidelines can help us both use GenAI effectively and support the development of critical AI literacy.

Human Directed

Human directed means using AI with purpose; using it to explore an idea, create something, or practice a skill. Instead of AI serving as a personalized tutor that tells learners what they need to learn and do, the learner is running the show. They employ their own agency to accomplish a task.

Using AI in this way can lead to powerful learning experiences–sort of like the generative learning idea I was exploring a few weeks ago. Learners can do more and learn from what they do. But this takes intentional, goal-driven interactions. This type of use requires active engagement–our next guideline.

Active Engagement

Because these tools present a different type of intelligence, interacting with them is unique. It calls for new habits of thinking and acting, and this takes a lot of effort to develop. Active engagement means practicing:

- Metacognition: Metacognition is thinking about thinking–and I would extend this to thinking about our experiences and emotions. This means becoming aware of when we might be making assumptions or when we are emotionally invested in a conversation. The latter is important because sometimes technologies hack our brains through manipulating the chemicals in them (think of social media addictions or games like Candy Crush Saga). We don’t yet know what impact these models will have on identity or mental and social health long-term. For now, trying to stay aware of how it might be impacting us can help us find balance and decide what is healthy and helpful use.

- Skepticism: I describe skepticism as a mindset of not accepting facts or information as automatically true. Sometimes this might be testing it to see if what we read or hear matches what we know, sometimes it might mean verifying information, and sometimes it is disregarding facts and focusing on ideas*. The important thing is to be aware that what we’re getting from GenAI is just correlations of words (or images, videos, sound), not verified facts.

- Reflection: Reflection is a key part of learning, it’s when we think back on something that happened and the results of that event. It might be reflecting on our own thinking, for example how our thoughts changed during a learning experience. It could also be reflecting on the results of something we tried out, such as a new prompt or AI application. The key is to have a habit of learning from what has happened and incorporating that into our new understanding of the world. It is not only the opposite of passiveness, it is also a way to expand ideas, make new connections, and come to see situations in different ways.

Metacognition, skepticism, and reflection can also include questioning the positionality we are seeing from the AI and that we are taking ourselves–whose story is being told? What perspectives are privileged and which are absent? How might these beliefs impact others, particularly those from traditionally marginalized populations?

Often supporting active engagement will take more than just trying to think during conversations. Learning might consist of going back over an AI chat and annotating observations, what was curious or weird or interesting, or what assumptions we might have made. I recently found it very useful to make a screen recording of an interaction, recording my thoughts out loud as I went, then going back to review. I also had a colleague, Suparna Chatterjee, review and see what they noticed about the conversation. I found patterns of thinking that I hadn’t picked up on in the original interaction, and my colleague provided additional insight and connection.

Reflecting with my colleague on an AI chat was a valuable experience–and another way to encourage this active engagement is to do it with other humans–collaborative exploration, which we turn to next.

Collaborative Exploration

Often when we think of technology in schools, we think of a learner working on their own device. Schools strive for one-to-one device-to-student ratios, emphasizing the need for all students to have access to digital technologies. While I believe that these are worthwhile goals, sometimes we miss the power of not having a device for each student, forcing them to work together and collaborate to accomplish tasks.

As we learn to interact with this alien intelligence, we need to support each other in our explorations while maintaining human connection and developing social skills. One powerful way to do this is to discuss with others what we are noticing during an interaction with AI. We can craft prompts together and analyze AI’s responses. The diversity of perspectives may help us be more aware of what is happening in the situation and develop the type of thinking we need to use AI tools appropriately and productively.

Learners also need modeling; they need others to show what active engagement looks like, how to practice skepticism, and how to analyze and evaluate AI outputs. Teachers can model this by working with a class or large group, talking out loud about their thought process while interacting with AI, asking students for prompt suggestions, and encouraging them to practice critical thinking. This scaffolding could then lead to a similar task in small groups, pairs, or think-aloud recordings, each step encouraging active engagement and critical thinking about the interactions.

Right now we are all learning, and we can embrace collaborative exploration as we work together to understand alien intelligence.

Creative Discovery

Finally, using AI in this goal-driven, brains-on, and social way expands possibilities for finding new applications and exploring new ideas. These alien intelligences can be just plain fun–experimenting to see what they will say and do, finding idiosyncrasies, and expanding what is possible for us to learn and do. When we begin discussing our thoughts and the things we notice with others, we can find new connections that can lead to new types of purposeful interactions with AI. Three brief examples:

- After hearing about Benford’s Law, I embarked on an exploration about how it might present itself in ChatGPT. This wasn’t a solo activity–my experiment was refined through conversations I had with others (specifically Nicole Oster and Punya Mishra). It was fun!

- Punya Mishra explored how ChatGPT might interpret an image he took during an eclipse. ChatGPT analyzed the image, described its observations, and connected them to scientific principles. With a bit more prodding, he was able to get it to predict when the picture was taken. The result was an exploration of both what ChatGPT could do and what an image can tell us about the sun and the moon during an eclipse.

- My friend Nicole Oster was reading about Goffman and face-work– how we manage our image in social contexts. She asked ChatGPT if it engaged in face-work and then engaged in a long conversation, full of skeptical questions and fascinating insight. She shared this with Punya Mishra and me, and Punya pointed her to a new essay by Kevin Roose about how Chatbots are being “tamed.” Nicole continued her conversation, connecting it to Roose’s essay, leading to new ways to think about AI. In this case, Nicole had a purpose: exploring Goffman’s face-work concept and how it intersected with AI; she interacted with AI with curiosity and skepticism, and she discussed what she was finding with others, leading to new connections.

I hope that thinking of GenAI in this way can help us as we look at the future of GenAI in teaching and learning. I’m sure I’ll refine these suggestions over time as I experiment with the ideas, but I hope they form a starting point for future experimentation and exploration.

*Disregarding facts reminds me a bit of the “hearsay” concept in legal trials; witnesses aren’t allowed to present truth based on what someone else said; they must rely on their own observations. However, sometimes witnesses can share what others have said–if the statement is not presented “for the truth of the matter” but rather to understand reactions or motives. Collaborating with AI is sometimes thinking in a sort of “post-truth” manner, using what it says to help you think and connect ideas, but not as proof of fact.